Osama Hazem flashed a huge grin. His younger brother Anas flashed one back.

The two were showing off photographs of their glory days as teenage Muay Thai competition fighters in Ramadi.

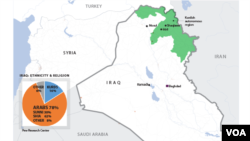

That was before Islamic State extremists stormed across vast strips of western Iraq, seizing their home and burning everything inside it. Like thousands of Iraqi Sunnis, Hazem and his brother refused to join the Sunni-dominated extremists.

So they ran away.

Hazem, his mother, sister, and two brothers, one of whom is disabled, now live crowded into one room of a rundown hotel in Kurdistan packed with displaced Sunni families.

Once a middle class family, the Hazems are broke.

Their new home, Shaqlawa, is a Kurdish town built in a small valley whose urban sprawl has edged into the hillsides. Cafes with red plastic chairs are full of Kurdish men drinking coffee and smoking. Nearby shops sell cheap fabric and discount merchandise.

But Hazem said that while displaced Arab-speaking Sunnis are tolerated, they not liked by the ethnic Kurds. On top of that, he can't find work, go to any sports clubs, and his family’s money is running out.

“Every day, every day we do nothing,” he said, sitting on one of three beds lining the bare hotel room walls. It was almost 48 degrees Celcius outside, and a small white fan connected to web of wires barely pushed the hot, heavy air around.

“We have been here for a year and a half, and we don’t have any jobs,” Hazem explained. “You know, if we stay here, in Iraq, our dreams and our future is all destroyed, all destroyed.”

Displaced, unemployed and bored

Josef Merkx, the UNHCR director for Kurdistan where Hazem and 1.3 million other displaced Iraqis have taken refuge, said international agencies were doing their best to help the youth.

In addition to jobs, Merkx said, “the youth of course is looking for recreation, for education, which is not readily available, so they may think of other things, even crime, or drugs, or violence.”

But with multiple displaced and refugee crises in the region, donor money to cope with the problem is limited. Merkx said in 2015 international funding had dwindled, making medium and long-term support for people like Hazem much more difficult.

“We have to focus on the most basic humanitarian assistance,” he said. “We can’t do things we also like to do: create better livelihood opportunities, to support better education, provision of health services.”

Kurdistan, a region of only five million people, has accepted about 1.3 million displaced people. Merkx said the region’s ability to cope with the influx is seriously stretched. Without more help, he said, those displaced could soon join the wave of migrants looking for help in Europe.

“We appeal for more international help as well, so we can help them in the region,” Merkx said.

A “5-Star” Camp is Still a Camp

Like Hazem’s family, the vast majority of displaced Sunnis escaped with some money, and live in hotels, rent out houses, or stay with friends and relatives.

But as the conflict in Iraq drags on, those families are running out of cash. An increasing number are asking to get admitted into the hundreds of aid agency-run camps around Kurdistan.

Baharka is a fenced-in, dusty “five-star” camp on the outskirts of Irbil with prefabricated shelters as well as tents with basic air conditioning, separate kitchen areas, and communal water taps.

Roughly half of the 4,000 people living in Baharka are teenagers. Hala, a dark-haired girl of 13, arrived at the camp about a year ago after escaping the Islamic State onslaught on her home city of Mosul.

Hala’s days have fallen into a monotonous routine of cooking and cleaning for her family, and getting together with other girls in the camp.

But the boredom is wearing on the youth.

Hala avoids the boys who have started bullying the girls as they walk through the camps dirt-packed roads, and says she misses school. Camp workers acknowledge that sexual harassment, alcohol abuse and violent behavior are a problem.

Camp directors and aid groups have established a small “drop-in” center where they offer some art classes, basic computer literacy and counseling. But there is limited space in the pre-fab rooms, and less than 10 computers for some 2,000 teenagers.

It’s not enough.

“I want to go to school, and I want to go back home,” Hala said.

But with no end in sight to the conflicts in Iraq, Hala doubts she will ever get back to her old life in Mosul.

“My life will remain the same. Just in prison,” he said.